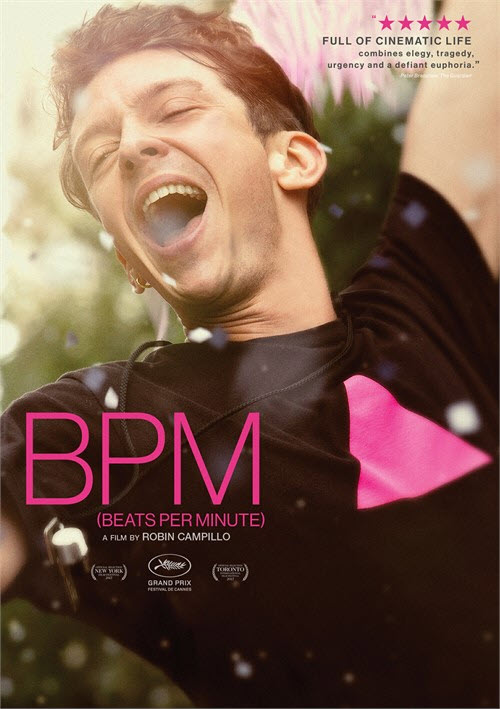

(2017, 140 min)

Country: France

Director: Robin Campillo

Studio: Passion River

Language: French w/subtitles

SYNOPSIS: In Paris in the early 1990s, a group of activists goes to battle for those stricken with HIV/AIDS, taking on sluggish government agencies and major pharmaceutical companies in bold, invasive actions. The organization is ACT UP, and its members, many of them gay and HIV-positive, embrace their mission with a literal life-or-death urgency. Amid rallies, protests, fierce debates and ecstatic dance parties, the newcomer Nathan falls in love with Sean, the group's radical firebrand, and their passion sparks against the shadow of mortality as the activists fight for a breakthrough.

BPM (Beats Per Minute) is one of the most acclaimed gay films of the year. The film won the coveted Queer Palm award at the Cannes Film Festival.

REVIEW:

As a remounting of Tony Kushner’s landmark opus Angels in America plays to raves in London, another loquacious, invigorating drama about the AIDS crisis is premiering at the Cannes Film Festival. Writer-director Robin Campillo’s deeply effective 120 Beats Per Minute is half sober and surveying docudrama, half wrenching personal illness narrative. Those two genres are fused together with an arresting artfulness, woozy and dreamy interludes mixing with the talky technical stuff to create a film that is broadly enlightening and piercingly intimate. It’s no wonder many are putting the film on the short list for the Palme d’Or.

Regardless of whether the film wins awards, it’s a vital contribution to queer and political cinema, a testament to crusaders of recent history whose nobility does not preclude their complicated and individual humanity. Campillo—whose last directorial effort, 2013’s alluring and mysterious Eastern Boys, is well worth watching—depicts a panorama of Parisians, many of them HIV-positive, as they strategize and bicker at ACT UP meetings, and as they dance and hook up and live lives as fully as their bodies will allow. The film’s approach to sex is admirably frank and even-handed, allowing for all its beauty and danger, its capacity for release, for connection, even for protest. One long, hushed bedroom scene in particular is downright stunning, a potent reminder of how rare it is to see this kind of physical and emotional exchange between gay people rendered so richly, so viscerally on film.

The organizing scenes are perhaps less enveloping, but they still hum with an urgent energy. Campillo is unafraid to show schisms and infighting, rashness and stubbornness. Many of the men and women involved in the cause were dying as they demonstrated and campaigned, and Campillo expertly illustrates how their idealism warred, or commingled, with a kind of pragmatic fatalism. It’s both devastating and heartening to watch, these horrifyingly young people bravely confronting vast and seemingly unmovable systems—government, pharmaceutical companies, etc.—while attending to their own fears, their own fragile mortality.

While we’ve seen this history reenacted before, most similarly in Larry Kramer’s seismic, furious jeremiad The Normal Heart, watching 120 Beats Per Minute never felt repetitive or redundant. Perhaps partly because I’d never seen the story told from the French perspective before, but mostly because Campillo and his fine company of actors imbue this history with such vivid immediacy.

The standout among the cast is the magnetic Nahuel Pérez Biscayart, who plays a brash, fiery activist named Sean with breathtaking conviction and clarity. As Sean’s illness gradually catches up to him, Biscayart maneuvers vast emotional terrain without losing sight of the person navigating it all. He doesn’t grandstand or awards-clip emote. He instead fits beautifully into the textured restraint of Campillo’s film, especially in one tender and bittersweet scene in which Sean and his lover, Nathan, accept the inevitable while also defying it. (The scene is another instance of Campillo addressing sex in truthful, humane ways.)

Nathan is played by Arnaud Valois, a hunky young actor who proves a persuasive, sensitive performer. He’s like a French Russell Tovey (currently starring in Angels in America in the West End), lantern-jawed and looming, but capable of striking vulnerability. Burgeoning actress Adèle Haenel—who was the lead in last year’s Cannes entry The Unknown Girl, from the Dardenne brothers—gives a centered, intelligent performance as fellow ACT UP member Sophie, while newcomer Antoine Reinartz perfectly calibrates the nerdy and needy sides of group leader Thibault. The whole cast is great, really, natural and vibrant and fluidly in step with one another. Biscayart, given the juiciest role, is just the knockout highlight, and I hope the Cannes jurors will keep him in mind when considering the best-actor prize.

And I hope this movie will be given the distribution and marketing it deserves, as the traumas of the 1980s and 90s fade in the rearview—even while AIDS rates are troublingly on the rise again. The film’s political and moral weight should not overshadow the artistry of its design, though, nor the quiet profundity of its unreserved and admirable approach to gay intimacy. Campillo has given his movie the breath of true life. It grieves and triumphs and haunts with abounding grace and understanding, its heartbeat thumping with genuine, undeniable resonance.

-- Review by Richard Lawson, Vanity Fair (vanityfair.com)