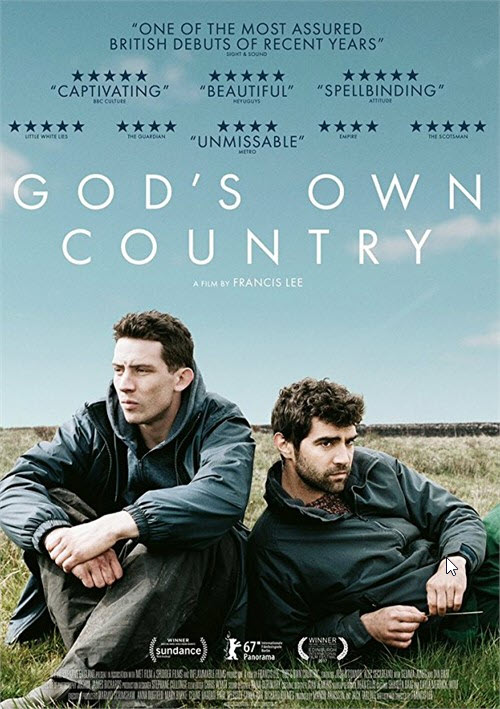

(2017, 104 min)

Country: U.S.

Director: Francis Lee

Studio: Samuel Goldwyn Home Ent.

Language: English

SYNOPSIS: Johnny Saxby (Josh O'Connor) works long hours on his family's remote farm in the north of England. He numbs the daily frustration of his lonely existence with nightly binge-drinking at the local pub and casual sex. But when a handsome Romanian migrant worker (Alec Secareanu) arrives to take up temporary work on the family farm, Johnny suddenly finds himself having to deal with emotions he has never felt before. As they begin working closely together during lambing season, an intense relationship starts to form which could change Johnny's life forever.

REVIEW:

British freshman helmer Francis Lee earns his 'Brokeback Mountain' quotations with a deeply felt gay romance set on the Yorkshire moors. In case it didn’t court “Brokeback Mountain” comparisons directly enough with its tale of two young sheep farmers finding love in a hopeless place, “God’s Own Country” seals the deal with one winkingly quoted shot: a work shirt draped on a wire hanger, poignantly removed from its wearer. Twelve years on, Ang Lee’s film has proven enough of a cultural milestone to merit such affectionate homage; luckily, Francis Lee’s tender, muscular Yorkshire romance has enough of an individual voice to get away with it. Skipping some of the more predictable narrative obstacles we’ve come to expect from the coming-out drama, this sexy, thoughtful, hopeful film instead advances a pro-immigration subtext that couldn’t be more timely amid the closing borders of Brexit-era Britain. Bolstered by a particularly sympathetic lead turn from rising star Josh O’Connor, Lee’s auspicious (if somewhat dourly titled) debut feature is hearty enough to land arthouse distribution beyond just the LGBT circuit — where it will, of course, be gladly embraced.

“What’s wrong with a night out in Bradford?” 24-year-old Johnny (O’Connor) asks his gruff man-of-the-soil dad Martin (Ian Hart), only to be sharply told that the very idea is “daft.” Johnny isn’t exactly shooting for the stars in attempting to broaden his life’s very narrow horizons, but Bradford may as well be Las Vegas compared to the daily grind on the failing family sheep farm in wind-lashed northern England. To his evident frustration, he shares a roof with Martin and his grandmother Deidre (the usually plummy Gemma Jones, cast against type to tersely moving effect), his mother long absent from the picture. With most of his peers having fled the region for brighter lights, Johnny’s social life is limited to nightly binge-drinking at the local pub, and swift, wordless sexual encounters with willing lads in the back of a van. When one of them dares to suggest they meet for a pint sometime, Johnny looks as incredulous as his father did earlier. A date with a guy? Don’t be daft.

So withdrawn is Johnny at the outset that several scenes pass before we even hear him speak, and to one of his livestock at that. When his father hires itinerant Romanian migrant worker Gheorghe (Alec Secareanu) to help with lambing season, Johnny regards the “gypsy” (in his unenlightened parlance) with little more than a sullen shrug. The surly dynamic between them shifts, however, when they’re sent to camp on the moors for several nights while they lamb the flock. Blame it on the (scant) sunshine, the moonlight or the sight of swarthily handsome Gheorghe tenderly cradling a weakling lamb, but the two men act impulsively on their attraction to each other, introducing Johnny to a physical and emotional temperature of intercourse he hasn’t previously known. Back at the farm, their relationship continues to blossom in private, though a tactful Deidre isn’t oblivious to the signs; when family misfortune increases Johnny’s responsibilities on the farm, the suspended reality of his hidden romantic life becomes harder to sustain.

What’s most bracing about “God’s Own Country” is the complex agency it grants its protagonist in unlocking his true desires. Rather than over-exerting well-worn clichés about rural homophobia, Lee’s script reveals pockets of tolerance in unexpected places; Johnny’s slowness to accept himself, meanwhile, seems the greater threat to his happiness. Intimacy doesn’t come naturally to man who has been raised in a household where caring is expressed through work; as captured in close-up by DP Joshua James Richards’ perceptive camera, even a gesture as innocuous as two fingertips grazing each other is a dramatic moment, practically accompanied by a silent fanfare of trumpets.

The repressed Englishman taught to love by a more worldly European? If it sounds a familiar dynamic, it is. Indeed, notwithstanding the sterner tone and setting of proceedings, certain key dramatic turns and reversals here play out much as they do in countless classical Hollywood boy-meets-girl stories. That Lee’s boy-meets-boy story doesn’t shy away from romantic convention feels, in its own way, rather progressive: “God’s Own Country” normalizes its characters’ love without a hint of sentimentality or sanctimony. Likewise, the film rousingly stands for the status and contributions of immigrants in the U.K. without recourse to political rhetoric. Gheorghe, who complains of his home country that “you can’t throw a rock without hitting an old lady crying for her children,” fills a practical need in a region itself abandoned by its young.

A standout in 2015’s “Bridgend” who has also clocked up appearances in “The Riot Club,” “Florence Foster Jenkins” and TV’s “Peaky Blinders,” O’Connor fulfils all his gangly promise as Johnny. Beautifully essaying subtle shifts in the character’s slouchy body language and reluctant speech, he exposes the character’s vulnerabilities and go-to defence tactics with brusque economy. He has thoroughly winning chemistry, meanwhile, with Secareanu, a strong, quietly imposing newcomer who gradually reveals a sense of playfulness and poetry behind the stoic exterior. Their love scenes, shot with casual clarity as they progress from animalistic rutting to more deliberate sensual exploration, are frankly hot without ever seeming cinematically choreographed.

Lee and Richards show little interest in prettifying the characters’ austerely spectacular surroundings, which look gustily, angrily gray even in the height of spring. Instead, they frame the landscape as oppressively or expansively as Johnny’s mood dictates. (The bucolic, brightly tinted archive footage of old-school farm labor that plays over the closing credits looks beamed in from another world entirely.) The emotional tenor of proceedings is faithfully tracked by a sparse, shivering score by American ambient duo A Winged Victory for the Sullen (one half of which, Dustin O’Halloran, is presently reaping plaudits for his work on “Lion”). By the time that tightly controlled soundscape blooms into the widescreen baroque pop of Patrick Wolf for the closing credits, the resulting heart-swell feels thoroughly earned.

-- Review by Guy Lodge, Variety (www.variety.com)