(2018, 94 min)

Country: U.S.

Director: Morgan Neville

Studio: Universal

Language: English

SYNOPSIS: For over 30 years, Fred Rogers, an unassuming minister, puppeteer, writer and producer, was beamed daily into homes across America. In his beloved television program, Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, Fred and his cast of puppets and friends spoke directly to young children about some of life's weightiest issues, in a simple, direct fashion. There hadn't been anything like Mr. Rogers on television before and there hasn't been since.

In an incredibly touching segment, co-star Francois Clemmons talks about coming out of the closet to Fred Rogers. The film also delves into the rumors about Rogers' own sexuality.

REVIEW:

By sheer coincidence — unless it is, somehow, a sign of the times — the two best American movies in theaters right now both happen to be about Protestant ministers grappling with their vocations in a fallen and frightening world. One of these men of the cloth is a fictional character, Ernst Toller, the anguished pastor (played by Ethan Hawke) who ministers to a dwindling flock in Paul Schrader’s “First Reformed.” The other is a real person: Fred Rogers, a graduate of the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary whose millions of congregants assembled in front of their parents’ television sets from the late 1960s until the early years of this century, absorbing his benign and friendly secular wisdom.

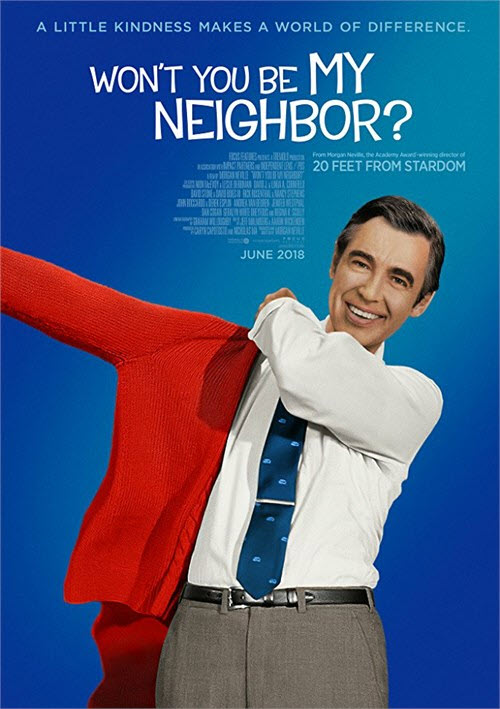

To them — to us — he was always and only Mister Rogers. The custom of this publication is to strip the dead of their honorifics (he died in 2003), but that feels almost blasphemous here. The “mister” signified that this man was a grown-up, that the friendship he offered his young fans wasn’t about condescending to us or compensating for his own lost youth. As he greeted us, he shed his suit jacket for a cardigan and traded his loafers for sneakers. But his tie stayed knotted, and his warmth carried an aura of gentle formality. He was not shy about being a role model or a benevolent authority figure. On the contrary, he took the responsibilities of adulthood seriously. He might have been the last of his kind.

A curious melancholy pervades “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?,” Morgan Neville’s moving and illuminating new documentary. A lump might gather in your throat during the opening titles and dissolve into sniffles and sobs as the final credits roll. Some of this can be ascribed to nostalgia. As a member of the charter generation of viewers — a toddler when “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” was first broadcast, in 1968 — I felt a bittersweet pang on revisiting the Neighborhood of Make-Believe, a place inhabited mainly by Mister Rogers’s puppet alter egos. It was delightful to see pictures of the low-budget set in the studios of WQED-TV in Pittsburgh, where the show started out, and to hear the reminiscences of members of the cast and crew..

The movie doesn’t dig too deep into its subject’s personal life. I remember wondering if there was a Mrs. Rogers. Her name is Joanne, and she and Fred raised two sons, John and James. They are interviewed on camera, adding detail and texture to the portrait of their husband and father. But not much is said about his childhood or his parents, though there is some mention of bullying and other early hardship. Mr. Neville, whose other films include “20 Feet From Stardom” and “The Best of Enemies” (directed with Robert Gordon) is not interested in psychological sleuthing. Rather than trying to unlock offscreen secrets, he sets out to assess the meaning and impact of an onscreen persona.

It is that emphasis — the earnest, critical attention to the public Mister Rogers and his legacy — that makes “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” feel like such a gift. Like Tom Junod’s great 1998 Esquire profile — the inspiration for a Mister Rogers biopic with Tom Hanks set for next year — this movie is at once unapologetically admiring and intellectually rigorous. (Mr. Junod shows up to add a few new insights and anecdotes.) It begins with an old clip of Fred Rogers, a trained composer, at the piano, explaining his approach to communicating with children by way of the musical concept of modulation. Some changes of key, he says, are easy enough to manage, while others are trickier. And so it is with feelings.

Several generations of American kids learned letters and numbers from “Sesame Street,” phonics from “The Electric Company,” and civics and grammar from “Schoolhouse Rock!” What Mister Rogers tried to teach us — how to navigate “some of the more difficult modulations” in everyday life — might now be classified as emotional literacy. He acknowledged that anger, fear and other kinds of hurt are part of the human repertoire and that children need to learn to speak honestly about those feelings, and to trust the people they share them with.

There was always an ethical — and, at times, a political — dimension to his calm, compassionate pedagogy. Early episodes of “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” tackled political violence and racial discrimination, and he could be a fierce critic of the commercial popular culture he deemed cruel, degrading or shallow. Part of the experience of growing up in his era was rebelling against his influence, and Mr. Neville gives some room to the satirists who pushed back against what could seem like a limiting and tyrannical niceness.

A few right-wing cable-news voices are also heard taking shots at Mister Rogers’s belief in the specialness of everyone, which they take as wishy-washy, character-sapping progressivism rather than a straightforward gloss on basic Christian teaching. What such critics see as a license for solipsism was in truth a call to recognize and respect the dignity of others.

A source of Mister Rogers’s charisma was his old-style conservatism. The Neighborhood of Make-Believe was a monarchy. The adjacent, “real” neighborhood, where he hung up his coat, fed his fish and chatted with Mr. McFeely and Officer Clemmons, was a utopian projection of the midcentury American small town, its problems not whitewashed but worked out, patiently and conscientiously, from one day to the next.

Mister Rogers’s demeanor balanced openness with reserve, curiosity with tact. The most radical thing about him was his unwavering commitment to the value of kindness in the face of the world that could seem intent on devising new ways to be mean. “Let’s make the most of this beautiful day,” he would sing at the start of each episode. He made it sound so simple, but also as if he knew just how hard it could be.

-- Review by A. O. Scott, NYT Critic's Pick (https://www.nytimes.com)